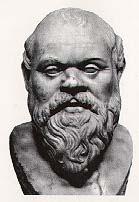

| 95b8 | [Phaedo is describing to his friend Echecrates the conversation between Socrates and his friends which took place before the death of Socrates.] |

date: 399 BCE

Socrates was 70

Plato was 28

|

| "`This is your main purpose, said Socrates to Cebes, to demonstrate that our soul is indestructible and immortal. Consider a philosophical man about to die, full of confidence, and believing that after death he will do better than if he had lived his life differently. Without a proof of the immortality of the soul, this man's confidence would be unintelligent and foolish. |

Socrates suggests that

Cebes believes that we

should fear death,

unless we can find a

proof that the soul is

immortal.

|

|

| 95b5

|

`As for showing that the soul is something strong and god-like, and that it existed even before we were born as human beings, you claim that all this may show, not immortality, but only that soul is long-lived and existed somewhere for an immense length of time in the past, and knew and did all kinds of things; even so, it was still not immortal. Indeed, its coming into a human body was the beginning of its destruction, like an illness: it lives this life in distress, and will indeed perish in what is called death. And you claim that it makes no difference, so far as our individual fears are concerned, whether it enters a body once or many times: it is appropriate for anyone who neither knows nor can give proof that it is immortal to be afraid, unless he has no sense. |

Cebes is said to think

that we need a proof, not that

there are immaterial souls

which last longer than

a single body, but

that they are immortal.

|

| 95e | `Something like this, Cebes, is what I think you're saying; and I am deliberately taking it up again and again, so that nothing may escape us, and so that you may add or take away, if you wish.' |

Is this an accurate

account of Cebes's

position ?

|

| 95e5 | And Cebes said: "No, there's nothing at present that I want to take away or add; and that is what I maintain." |

Yes

|

| 96a | So Socrates, having paused for a long time for reflection, said: "What you're searching for, Cebes, is no trivial matter. It needs a thorough and comprehensive review of the reasons* for coming into existence and passing out of existence. So, if you like, I shall go through my own experiences on these matters. Then, if any of the things I say seem helpful to you, you can use them as a means of persuasion for your points." |

Socrates says that there

is a more general question

first: why does anything

exist, come into existence

or cease to exist ?

*"aitia": reason, cause,

responsibility, blame,

explanation

|

| "Well, I certainly should like that," said Cebes. |

| 96a6 | `Then listen to my story. When I was young, Cebes, I was fantastically keen on science; it seemed to me marvellous to know the reasons for everything, why things come into existence, go out of existence, or exist at all. |

Socrates and "science"

(a form of "wisdom"

called "the

investigation of nature")

|

| 96b

|

I kept changing my interests, but at first I was keen on looking at questions like these: "Do living creatures arise from the putrefaction caused by the warm and the cool coming together ?" And "is it blood that we think with, or air, or fire? Or is it none of these, but instead the brain makes perception possible (hearing and seeing and smelling); from this memory and judgement come into being; and is it from memory and judgement, when they are settled, that knowledge in its turn comes into being ?" |

e.g. how do life,

thought, and knowledge

come into existence?

|

| 96c | Next, when I went on to examine how these things pass out of existence, and what happens in the heavens and the earth, I finally judged myself to have absolutely no gift for this kind of inquiry. |

Socrates claims that

he was no

good at "science"

|

| 96d

|

I'll tell you something which shows this well enough: there had been things that I previously did know for sure, at least as I myself and others thought; but I became so thoroughly blinded by this investigation, that I unlearned even those things I formerly supposed I knew, including, among many other things, why it is that a human being grows. I used to think that this was obvious to everyone: it was because of eating and drinking; something small became bigger, whenever, from food, flesh was added to flesh, and bone to bone, and similarly on the same principle the appropriate matter was added to each of the other parts; and it was in this way that the small human being comes to be large. That was what I supposed then: reasonably enough, don't you think ?' `Yes,' said Cebes. |

explaining growth

|

| 96e

|

`Well, consider these further cases. Take a large man or horse standing

beside a small one, and the one is obviously bigger than the other by a

head. I used to think that this description was enough. And,

to take cases even clearer than these, it seemed to me that ten was greater

than eight by having an extra two, and the two cubit item was greater than

the one cubit item, because it exceeded the latter by half.'

`Well, what do you think now ?' said Cebes. |

comparative sizes

|

| 97a

|

`I don't have the faintest idea of the reason for these things. I don't even accept from myself that when you add one to one, it's either the one to which the addition is made that has come to be two, or the one that's been added and the one to which it's been added, that have come to be two, because of the addition of one to the other. Because I wonder if, when they were apart from each other, each was one and they weren't two then; whereas when they came close to each other, this then became a reason for their coming to be two, the union in which they were put together. |

addition is not

"bringing together"

|

| 97b

|

Nor can I any longer be persuaded, if you divide one, that division has now become a reason for its coming to be two; because if so, we have a reason opposite to the previous one for its coming to be two; then it was their being brought close to each other and added, one to the other; whereas now it's their being drawn apart, and separated each from the other.I can't even persuade myself any longer that I know why it is that `one' comes into being; nor, in short, why anything else comes into existence, passes out of existence, or exists at all, following that method of inquiry. Instead I was been bold enough to set aside this method, and adopt another one. |

physical explanations

of these phenomena

are unsatisfactory

|

| 97c | `One day, however, I heard someone reading from a book he said was by Anaxagoras, according to which it is, in fact, mind that orders and is the reason for everything. |

Anaxagoras

(500-428 BCE)

|

|

97d

|

Now this was a reason that pleased me; it seemed to me, somehow, to be a good thing that mind should be the reason for everything. And I thought that, if this were so, then mind, in ordering all things must order them and place each individual thing in the best way possible; so if anyone wanted to find out the reason why anything comes into existence or passes out of existence or exists at all, what is need is to find out how is it best for that thing to exist, or to act or be acted upon in any way. On this theory, then, a man should consider nothing else, whether in regard to himself or anything else, but the best, the highest good; though the same man must also know the worse, as they are objects of the same knowledge. |

If Mind orders

everything, it

must order

everything for

the best,

Socrates supposes,

|

| 97e

98a |

Reasoning in this way, I was pleased to think I'd found, in Anaxagoras, a teacher who suited my own way of thinking about the reasons for things existing. I thought that he would tell me, first, whether the earth is flat or round, and after telling me, that he would go on to explain the reason why it must be so, telling me what was better, and that it was better that it should be such; and if he said it was in the centre, he would go on to explain why a central position for it was better. If he could make these things clear to me, I was ready to give up looking for other kinds of reason. |

Socrates assumes

that Anaxagoras

would explain the

shape of the earth

by showing that

this was the best

shape for it.

This would satisfy

Socrates.

|

|

98b

|

What's more, I was prepared to find out in just the same way about the sun, the moon, and the stars, about their relative velocity and turnings and the other things that happen to them, and how it's better for each of them to act and be acted upon just as they are. For I never thought that, since he claimed that they were ordered by mind, he'd bring in any reason for them other than its being best for them to be just the way they are; and I thought that in giving the reason for each individual thing, and for things in general, he would go on to explain what was best for the individual, and what was the common good for all. |

Compare Leibniz's

"Principle of

Sufficient reason"

|

|

98c |

These hopes were dear to me, and I made an effort to get hold of the

books and read them as quickly as I could, so that I might know as quickly

as possible what was best and what was worse.

`Well, my friend, these marvellous hopes of mine disappeared. It turned out, as I went on with my reading, that there was a man making no use of his mind at all, nor finding in it any reasons for the ordering of things, but explaining them by such things as air and aether and water and many other out of place things. |

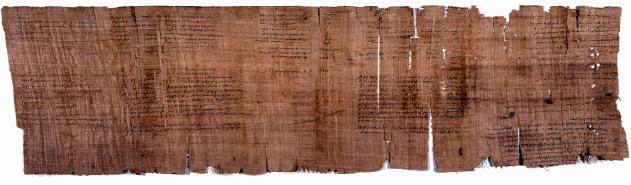

Socrates was

disappointed by the

"books" (books were

then expensive and

rare papyrus rolls).

|

|

98d

|

In fact, he seemed to me me exactly like someone who said that everything that Socrates does involves his mind, but then explained each of my actions by saying, first, that the reason why I'm now sitting here is that my body consists of bones and sinews, and the bones are hard and separated from each other by joints, whereas the sinews, which can be tightened and relaxed, surround the bones, together with the flesh and the skin that holds them together; so that when the bones are turned in their sockets, the sinews by stretching and tensing enable me somehow to bend my limbs at this moment, and that's the reason why I'm sitting here bent in this way. |

an anatomical

explanation of

why Socrates is

sitting there

|

| 98e | Or again, why am I now talking to you ? He would give other reasons of the same kind, vocal sounds, air currents, auditory sensations, and countless other such things, yet neglecting to mention the true reasons: that Athenians judged it better to condemn me, and therefore I in my turn have judged it better to sit here, and thought it more just to stay behind and submit to the penalty which they have determined. |

Why is Socrates

talking to his friends

now ? Because

he decided that it

was right to accept

the punishment

determined by

his fellow-citizens..

|

| 99a

|

Heavens, I guess that these sinews and bones would long since have been off in Megara or Boeotia, impelled by their judgement of what was best, had I not thought it more just and honourable not to escape and run away, but to submit to whatever penalty the city might impose. |

Otherwise, he

could have gone

to another city.

|

|

99b |

But to call such things "reasons" is extremely inappropriate. It would be quite true to say that without possessing such things as bones and sinews, and whatever else I possess, I shouldn't be able to do what I judged best; but to say that it is because of these things that I do what I do, acting intelligently, and not my choice of what is best, is loose talk. |

Properly speaking,

my anatomy is a

condition, but not

a reason for

my sitting.

|

| 99c

|

Think of not being unable to distinguish two different things: the

real reason, and those other things without which the reason could never

be a reason! Yet I suppose most people do call these things reasons;

groping at them in the darkness, as it seems, and giving them the name that belongs to something else, and calling them reasons. That's why some people put a vortex around the earth, making it stay in its position by means of the heavens; while others put the air underneath as a support, like a flat kneading-trough. Yet the power by which they're now situated in the best way that they could be placed, this they neither look for nor credit with any supernatural strength; but they think they'll one day discover an Atlas stronger and more immortal than this, who does more to hold everything together. That it's the good or binding, that genuinely does bind and hold things together, they don't believe at all. |

We need

explanation

in terms of

the Good.

|

| 99d | Now I should most gladly have become anyone's pupil, to learn the truth

about a reason of that sort; but since I was deprived of this, proving

unable either to find it for myself or to learn it from anyone else, would

you like me, Cebes,d to give you a display of how I've conducted

my second voyage in search of the reason?'

`Yes, I'd like that immensely,' he said. |

The second voyage

|

| 99e

100a |

`Well then,' said Socrates, `it seemed to me next, since I had given up looking at the things that are, that I must be careful to avoid what happens to people who observe and look directly at the sun during an eclipse; some of them, you know, ruin their eyes, unless they look at its image in water or something like that. I had a similar thought: I was afraid I might be completely blinded in my soul, by looking at objects with my eyes and trying to grasp them with each of my senses. So I thought I should take refuge in words*, and study in them the truth of the things that are. Perhaps my comparison is, in a certain way, inept; for I don't at all concede that one who looks at the things that are in words is any more studying them in images than one who examines them in concrete. |

logoi:

words, accounts

propositions

Socrates decides

to look for truth

through language.

|

|

|

But anyhow, this was how I started off: hypothesising on each occasion

the proposition (logon) I judge strongest, I posit as true

whatever seems to to me to harmonise with it (both about

reasons and about everything else); and whatever does

not, I put down as not true. But I'd like to explain my meaning more

clearly; because I don't think you have understood

me this time.'

`Not at all, by Heaven!' said Cebes. |

using the

hypothetical

method

|

| 100b

100c |

`Well,' he said, `this is what I mean: it's nothing new, but

what I've spoken of constantly in our earlier discussion as

well as at other times. I'm going to set about displaying to you

the kind of reason I've been dealing with; and I'll go back to those much

talked-about things*, and start from them, hypothesizing

that there is some beautiful, itself by itself, and good and large

and all the rest. If you grant me that and agree that those things

exist, I hope that from them I shall display to you the reason,

and find out that soul is immortal.'

`Well, you won't be jumping to conclusions, if you take that for granted,' said Cebes. |

and the

theory of "Forms" |

| 100d

100e

|

`Then look at what comes next to those things, and see if you

think as I do. It seems to me that if anything else is beautiful

besides the beautiful itself, it is beautiful for no reason at

all other than that it shares in that beautiful; and the same goes

for all of them. Do you agree to a reason of that kind?'

`I do.' `Then,' said Socrates, `I no longer understand nor can I recognize those other clever reasons; but if anyone gives me as the reason why a given thing is beautiful either its having a blooming colour, or its shape, or something else like that, I dismiss those other things-because they confuse me-but in a plain, untechnical, and possibly foolish way, I hold on to this, that nothing else makes it beautiful except that beautiful, whether by its presence or communion or whatever the manner and nature of the relation may be; as I do not yet take a strong position on that, but only affirm that it is by the beautiful that all beautiful things are beautiful. For that seems to be the safest answer to give both to myself and to another, and if I hang on to this, I believe I'll never fall: it's safe to answer both to myself and to anyone else that it is by the beautiful that beautiful things are beautiful; or don't you agree?' `I do.' |

Things are

beautiful

because of their

relation to the

Form of Beauty

(the beautiful

itself).

|

| 101a

101b

101c

101d |

`And it's by largeness that large things are large, and

larger things larger, and by smallness that smaller things are smaller?'

`Yes.' `Then you too wouldn't accept anyone's saying that one man was larger or smaller than another by a head, but you'd protest that you for your part will say only that everything larger than something else is larger by nothing but largeness, and largeness is the reason for its being larger; and that the smaller is smaller by nothing but smallness, and smallness is the reason for its being smaller. You'd be afraid, I imagine, of meeting the following contradiction: if you say that someone is larger and smaller by a head, then, first, the larger will be larger and the smaller smaller by the same thing; and secondly, the head, by which the larger man is larger, is itself a small thing; and it's surely monstrous that anyone should be large by something small; or wouldn't you be afraid of that?' `Yes, I should,' said Cebes, with a laugh. `Then wouldn't you be afraid to say that ten is greater than eight by two, and that this is the reason for its being larger, rather than that it is by size and because of its size ? Or that two cubits are larger than one cubit by half, rather than by magnitude ? For, of course, there'd be the same fear.' `Certainly,' he said. `And again, wouldn't you beware of saying that when one is added to one, the addition is the reason for their coming to be two, or when one is divided, that division is the reason ? You would exclaim that you know no other way in which each thing comes to be, except by participating in the peculiar Being of any given thing in which it does share; and in these cases you have no other reason for their coming to be two, save sharing in twoness: things that are going to be two must share in that, and whatever is going to be one must share in oneness. You'd dismiss those divisions and additions and other such subtleties, leaving them as answers to be given by people wiser than yourself; but you, scared of your own shadow, as the saying is, and of your inexperience, would hang on to that safety of the hypothesis, and answer accordingly. |

And things are large

or larger because of

their relation to

Largeness, etc.

|

| 101e | But if anyone hung on to the hypothesis itself, you would dismiss him, and you wouldn't answer till you had examined its consequences, to see if, in your view, they are in accord or discord with each other; and when you had to give an account of the hypothesis itself, you would give it in the same way, once again hypothesizing another hypothesis, whichever should seem best of those above, till you came to something adequate; |

The hypothetical

method leads to

"something adequate".

|

| 102a | but you wouldn't jumble things as debaters do, by discussing

the starting-point and its consequences at the same time, if, that

is, you wanted to discover any of the things that are. For them,

perhaps, this isn't a matter of the least thought or concern; their

wisdom enables them to mix everything up together, yet still be pleased

with themselves; but you, if you really are a philosopher, would, I imagine,

do as I say.'

'What you say is perfectly true,' said Simmias and Cebes together." |

It is necessary to

reason clearly and

systematically.

|

[This is the end of this report by Phaedo to Echecrates of what Socrates said to his friends, according to Plato's account. Shortly afterwards, there is another report of the attempted proof of the immortality of the soul subsequently given by Socrates.]